The relation between the necessary and simultaneously sufficient number of respondents and the detectability of usability problems have long aroused understandable emotions.

As Jakob Nielsen himself wrote more than twenty years ago:

"Elaborate usability tests are a waste of resources. The best results come from testing no more than 5 users and running as many small tests as you can afford."

It would be improper not to believe a man who is a precursor of User Experience has a very sober and pragmatic approach and shows useful skepticism and caution.

Nielsen's approach, which was treated as a certainty in UX for a long time, has lived to see skeptical stances and, in some cases, openly critical.

Thus, our Dear Reader, if you don't want to take Jakob Nielsen's statements on faith and need arguments, "pros and cons," then read this article.

We will discuss the arguments of supporters of usability testing with only 5 respondents, and we will take a closer look at the opinions of the critics of this approach.

In recent years critical voices have been aroused, and it's worth learning about this line of argumentation and interpretation of the problem.

Intellectual honesty requires it, and the quality of the decisions made based on the research results also depends on it.

Because the matter doesn't seem as clear as Jakob Nielsen would want it to be, the detectability of the problem and the size of the sample — it's a relationship worth exploring.

After familiarizing yourself with both stances on this matter, you can decide which one you prefer and which will be the most beneficial for a given research problem or design.

So, are five users, respondents enough to confidently determine whether the research yielded reliable results that will allow you to make the most optimal design decisions?

If five users are not enough, then why is that?

What is the minimum number of respondents that should be considered to obtain the expected results when performing a website usability test?

Is the number of respondents tailored to the purpose of the research? Are we talking about special cases or a research standard? — These are our questions.

We cordially invite you to read the article.

User Testing, Usability Testing, or a brief discussion about UX Research

In most cases, usability testing (e.g., of a website), usability tests, and UX research are performed with quantitative research, qualitative research, or mixed methods.

UX research and usability testing with users, representatives of the target group are usually performed stationary or remotely. They can be moderated or unmoderated.

There are at least a dozen research methods that can help you conduct a user test.

However, in the matrix defined by the axis Qualitative Research vs. Quantitative Research, Behavioral (What people do) vs. Attitudinal (What people say), you can often find around nine most popular methods.

We mention this because you shouldn't separate the problem of the number of respondents from the subject of the study or its method.

It's also worth keeping in mind that whether you will refer to quantitative research, qualitative research, behavioral research, or attitudinal research, the results of the test should serve to make the best possible:

- Design decisions

- Business decisions

- Strategic decisions that determine the competitiveness of the digital product.

The results of the tests, research, and observable reactions of users provide specific information that allows you to improve and optimize the website and make it more intuitive.

More or less successfully.

Elements such as the research scenario, the course of the study, research questions as well as leading questions in interviews with users (allowing you to obtain more specific information), conditions, contexts of the performed research, research tools, and the ability to observe have an influence on the results and reduce or increase control over it.

Test results (particularly usability testing) are a recommendation regarding changes. As you know, changes involve risk, responsibility, budget, time, and many other issues.

It is widely known that the goal of most stakeholders, among others, UX/UI designers, UX researchers, and business owners, is to achieve credible results of the tests with users in a short time.

With minimal funds and resources.

The economization (in a financial, time, and organizational sense) of the research, design, optimization, and development process is, for obvious reasons, understandable.

However, is it always a justified and beneficial approach?

User testing that involves only five respondents seems to fulfill these needs ideally.

Due to economic and organizational reasons, it's hard to resist the temptation to ignore arguments that recognize the greater legitimacy of conducting a more extensive study.

How does it look in practice? Who is right in this dispute?

Why you only need to test with 5 users — the approach of Jakob Nielsen from NN Group

Nielsen's stance has been known for decades, and to a small extent, it was modified over the past 30 years.

The co-founder of NN Group defends his approach.

His stance is very well illustrated by the articles published on his parent company's site.

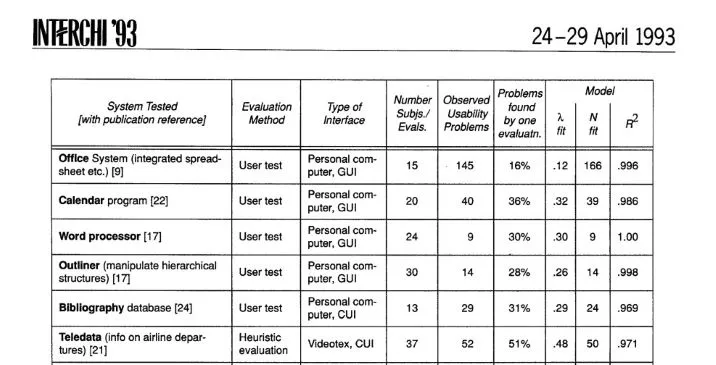

If you want to familiarize yourself with the originals, consider the following articles: "Why You Only Need to Test with 5 Users," whose author is Nielsen, and "A mathematical model of the finding of usability problems," written by Nielsen and Thomas K. Landauer, and "How Many Test Users in a Usability Study," "Quantitative Studies: How Many Users to Test?" also by Nielsen.

To broaden your perspective, you should also read the article of Raluca Budiu from NN Group, "Why 5 Participants Are Okay in a Qualitative Study, but Not in a Quantitative One."

With such a corpus of texts, we can summarize the main arguments put forward to defend the approach of 5 users.

Above all, Nielsen is a supporter of the economization of research. He thinks that the opposite approach is wasteful and thus unnecessary and what's most important unjustified.

Or at least he considers it unreasonable and demanding a different approach, but we will write about this later.

Nielsen bases his argumentation on a proprietary model that allows mathematically and thus objectively, impartially, measurably, and precisely determine the dependency between the number of people necessary for research and the number of usability problems.

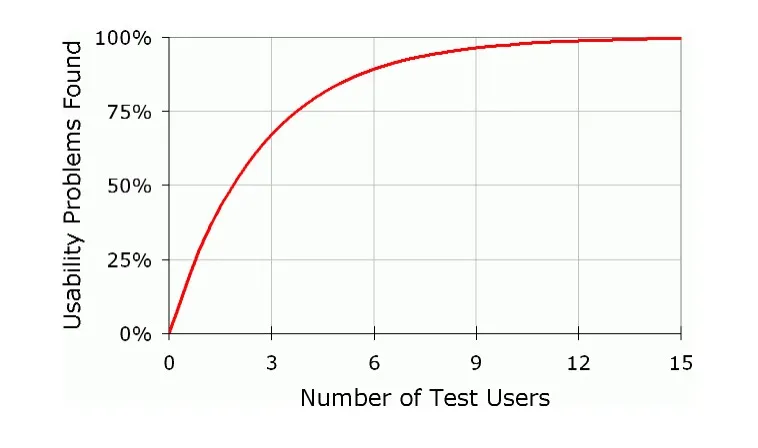

According to Nielsen and Landauer's model — N (1-(1- L ) n ) — 100% of problems with usability can be discovered by performing studies with 15 users, and only 5 respondents are needed to achieve an 85% detection rate.

It is worth quoting Nielsen, who rightly points out that just one respondent can provide knowledge about problems with usability at the level of 30%.

With each successive user, the increment of new knowledge and newly discovered problems doesn't rise this dynamically because some issues simply overlap and duplicate. After the fifth user, you're not gaining any new data.

As Nielsen notes:

"As you add more and more users, you learn less and less because you will keep seeing the same things again and again. There is no real need to keep observing the same thing multiple times."

Then why does Nielsen dig his heels in and sticks with 5 and not 15 respondents?

Because he thinks that it's more effective to iterate the design and research processes.

According to Nielsen, detecting 85% of problems is better than 100%. Correct the design and then perform the research again. Repeat the process. Instead of conducting one study with 15 respondents, it's better to perform 3 studies at 3 stages of the design with 5 respondents in each study.

Nielsen is convinced that such an approach enables the elimination of the problem of the research shadow in the form of 15% of issues whose importance and significance can decide about success or failure.

According to his optimistic approach:

"The second study with 5 users will discover most of the remaining 15% of the original usability problems that were not found in the first round of testing".

"As soon as you collect data from a single test user, your insights shoot up and you have already learned almost a third of all there is to know about the usability of the design."

Nielsen's approach, and he is aware of that, but doesn't regard it as that significant, is justified when the target group is homogeneous.

If you're dealing with a couple of user groups and, in reality, it's a norm. You will have to perform the first tests with the representatives of each group.

In summary, Nielsen's cardinal argument is an argument that doesn't so much relate to the detection itself as to its effects, profits and losses, ability to optimize research and economize its utility.

Nielsen, at every opportunity, states firmly:

"Testing with 5 people lets you find almost as many usability problems as you'd find using many more test participants."

At the same time, over the years, he corrected his approach. He made it more contextual and connected to the cause-and-effect relationship between the number of respondents and the type of research and detectability.

According to his revised approach, he points out exceptions.

Namely:

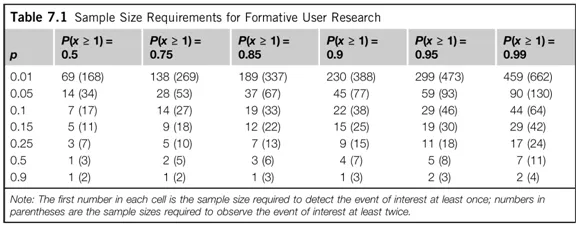

- For quantitative research, you'll need at least 20 users

- For card sorting — 15 users

- For eye-tracking — 39 users.

While dismissing arguments of the supporters of the larger number of respondents, Nielsen points out the main argument, namely, the return on investment (ROI), and somewhat over-absolutizes it.

The article by Raluca Budiu is a good summary of Nielsen's approach. Budiu, in a condensed form, presented three crucial arguments which should convince everybody to perform research with 5 users.

These 3 main arguments are:

- Qualitative research and tests with users don't serve to predict how many people will have problems with the usability of a website, but they're used to identify the problems with usability.

- A single occurrence of a problem does not require quantitative confirmation — one issue for one person is an issue for everybody.

- The probability that someone will encounter a problem is 31%.

This, of course, raises the problem of the statistical and simultaneously business significance of such discoveries, which the author is aware of.

A problem that repeats in 1000 cases for 1000 site users and not 1 time in 1000 cases is naturally more critical and potentially more harmful.

Determining this relationship, of course, requires using quantitative methods, which Badiu doesn't deny, but neither does she consider it necessary, again referring to the waste and economization of research.

Is this the right approach? Now let's give the floor to its critics.

It's not enough to test with 5 users — a critical approach to Jakob Nielsen's model

Jakob Nielsen isn't infallible, and every substantial criticism supports knowledge development and allows you to choose more consciously and with a more profound understanding of consequences. It enables you to make a profit and loss statement.

Regarding the critical approach, we can also present a corpus of texts from different authors, and we warmly encourage you to familiarize yourself with original articles.

Above all, it's worth reading the following articles "5 Reasons You Should and Should Not Test With 5 Users," written by Jeff Sauro, and "Five, ten, or twenty-five. How many test participants?" authored by Ellen Francik and "The 5 User Sample Size myth: How many users should you really test your UX with?" by Frank Spillers.

The first two texts have a more academic character. The third one is valuable because of its insider nature, pointing out the practical challenges that multiply in the design and research process.

The objections to the testing model with 5 respondents mainly concern the following issues:

- The lack of ranking of detected problems.

- Absolutizing the repeatability of problems with usability and their significance, 85% of detected errors by five respondents don't have to be the most critical problems from the perspective of user experience, sales, business process, or strategy.

- "Sensitivity" of this method — five respondents will discover the majority of obvious problems if the problem with usability applies to at least 31% of all users.

- More specific problems require a larger sample — it's worth remembering, and it's easy to confuse these issues, that five respondents won't discover 85% of all the problems but only 85% of the most evident issues. Although these problems are significant, it doesn't mean that the remaining 15% can be considered less critical.

- In the case of tests that measure the percentage of respondents who finished the task, to achieve a statistically correct view of the situation — margin of error within +/-10% — you have to test 80 respondents.

- With a small sample, it's harder to determine the usability of a website than its uselessness. In other words, the small number of respondents can direct the findings and enhance the biased conclusions and assessments.

Ellen Francik provided interesting arguments that make Nielsen's approach problematic by citing research showing that the Nielsen curve does not always run like a Swiss watch.

Francik writes:

"Perfetti and Landesman (2001) tested an online music site. After 5 users, they'd found only 35% of all usability issues.

After 18 users, they still were discovering serious issues and had uncovered less than half of the 600 estimated problems.

Spool and Schroeder (2001) also reported a large-scale website evaluation for which 5 participants were nowhere near discovering 85% of the problems."

These discrepancies are understandable if you pay attention to how confusing the research category, as viewed by Nielsen, is.

Primarily it's not specific.

Website usability testing with users/target groups is never research per se, only a targeted, fragmented, and narrowed study. Hence, this mythical 85% applies not to the whole but, most often, to a fragment. No research method would allow you to study the whole system, but that's another issue. Each omits, doesn't see, exaggerates, or abstracts something.

Remember that research practice and theory are two different worlds.

And every study of a target group has its limitations regarding the following:

- Time — extensive systems can't be examined thoroughly during standard study time.

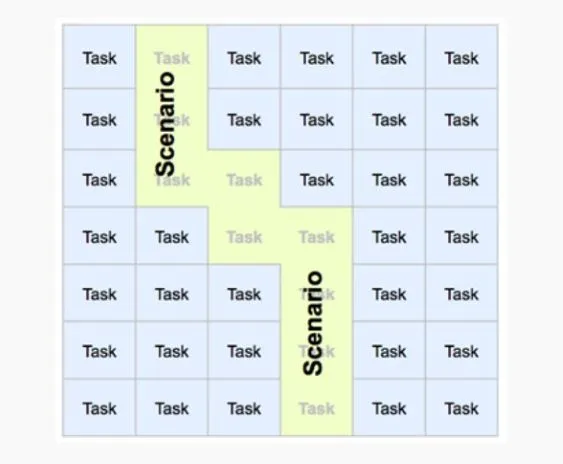

- Tasks — in the case of extensive systems, the most frequently selected use scenarios and chosen functionalities are examined (UX research/tests are targeted).

- Detectability — the detectability of errors decreases along with the number and diversity of possible paths leading to achieving a given task. Websites where a given task can be completed in only one perfectly determined way are rare.

- The distribution of the detection of common, moderately frequent, and rare problems is proportional to the sample size.

What's even more important the detectability of usability problems is not only a matter of the number of respondents. That's a very harmful reductionism and simplification.

The following factors also influence the detectability of problems with usability:

- The number and experience of researchers who can correctly perform the study, UX tests, website usability testing, and UX research.

- Stage of development of the design — the more perfect the design in terms of usability, the more difficult the detectability of problems, and the issues themselves are much more atypical, subtle, and less evident.

- Experience of users — the more experienced users are, the easier it is for them to use the system for their own purposes. However, something more complicated is a problem for them.

- Definition of a problem formulated by users — diverse competencies and experiences influence what is considered a problem and what rank is given to it.

- Homogeneity and representativeness of respondents.

- The complexity of a task, its typicality.

- Duration of research and the number of tasks planned for the study — the tendency to see or ignore problems depends on the level of fatigue of respondents caused by the study.

We should add to the abovementioned issues purely practical problems not related to the ideal, model image of research but to its real course.

The problem of detectability is also related to the following:

- The quality of recruitment for UX research

- Engagement in the UX research of the researcher themselves

- Tendency to avoid more specific problems in the process of categorizing, analyzing, and interpreting data

- Organizational challenges — Nielsen's iterative approach to UX research is, to a large extent, an idealistic approach that faces many obstacles in real-world conditions.

Frank Spillers asks a telling and blunt rhetorical question:

"With 12 users, you would have 4 rounds of design changes and 4 user tests. Show me an Agile development team in the world, that would permit that level of disruption and protracted testing?".

He adds in a similar vein:

"Even 3 smaller studies are likely to not scale to the realities of most projects".

However, this is not the end of counterarguments against Nielsen's model.

Nielsen's approach is also criticized because of the following:

- Anachronism — the basis of his model was formulated a few decades ago, in entirely different conditions and in the early stages of User Experience research development

- Harmful universalism — it doesn't consider the specifics of different audiences, channels, and devices, and the differences between applications (e.g., the concept of a website is problematized minimally)

- The lack of consideration of the roles that users play when using the site, which significantly affects the scope, number, importance, and rank of the problems they report

- The lack of inclusion of sensitivity to the problem of UX research respondents — a usability problem is not something that affects everyone in the same way, in the same sense, scope, and weight.

A fascinating and simultaneously summarizing all objections directed at Nielsen's model is the article "Beyond the five-user assumption: Benefits of increased sample sizes in usability testing," written by Laura Faulkner, an American author associated with the University of Texas.

Faulkner compared tests with a different number of users. According to her results, it turned out that there is a considerable risk of getting inaccurate results when you put too much faith in Nielsen's model.

In some tests with 5 respondents, detection rates of 99% were achieved, while in others, the rate was 55%.

The doubling of the sample size caused the lowest percentage of problems revealed by one set to rise to 80% and 95% in the case of 20 users.

How to recruit participants for Usability Testing?

Since we already discussed the pros and cons of conducting user testing with 5 users, we should at least briefly mention how to recruit participants for it.

According to the article on the Interaction Design Foundation blog "How to Recruit Users for Usability Studies," you can use five methods for recruiting participants for remote usability testing or in-person usability testing.

Namely the following:

- Hallway or Guerrilla Testing — This method involves asking people around you to join your testing group. Although it looks like an easy way to acquire "free participants," these people most likely won't reflect your target audience well.

- Existing users — If you want to test an already existing product or service, the user base you already possess is perfect for that. Thanks to that, you will gain valuable insights and collect data that is relevant to your product.

- Online service recruitment — Interaction Design Foundation recommends three online services that can help you recruit research participants, and these include Craigslist, Usertesting.com, and Amazon Mechanical Turk.

- Panel Agencies — They possess vast databases of users willing to take part in remote usability testing (unmoderated), which allows you to select the right participants.

- Market research recruitment company — It's the most expensive recruitment method, but a company will provide you with considerable help in selecting the best-suited participants.

If you want to learn about the above methods in more detail, we encourage you to read the mentioned article so that you can assemble the best possible test group for your user testing.

Why is it enough to test 5 users? Summary

- According to Jakob Nielsen from NN Group, expanded usability tests (of an online store, for example) are a waste of resources.

- Nielsen supports the economization of research. He thinks that the economization of the research and design process is, for obvious reasons, understandable and should be taken as an absolute value.

- He considers the opposite approach to tests with users as wasteful and unjustified.

- According to Nielsen and Landauer's model, which was created in 1993, 100% of usability problems can be detected by performing studies with 15 users.

- To achieve 85% detectability through testing with users, you only need 5 respondents.

- When you add more test users, the discovered usability problems duplicate.

- According to Jakob Nielsen, instead of conducting one study with 15 respondents, it's better to perform 3 studies at 3 stages of the project with 5 respondents in each study.

- Nielsen's argument is an argument that doesn't so much relate to the detection itself as to its effects, profits and losses, and ability to optimize research and economize its utility.

- The arguments that should convince everyone to test with 5 respondents are the purpose of the research, which is to identify problems, the universality of the problem, one problem for one person is a problem for all people, and that there is a 31% probability that someone will encounter a problem.

- Nielsen's approach is primarily criticized due to, among other things, the anachronism, harmful universalism, lack of consideration of the users' roles, and the lack of inclusion of sensitivity to the problem of respondents.