Modern science relies on research problems, questions, hypotheses, experiments, replication of research, and meta-analysis.

Research methods, UX research, and usability testing (qualitative research, quantitative methods) are based on research questions.

To conduct UX research, first and foremost, we must ask good research questions.

Relevant problems and research questions are the starting point and form the horizon of our knowledge of the world and phenomena.

Problems and research questions organize knowledge and establish research trends for years to come (including within user experience research), bringing to life entire schools of research or more detailed approaches.

They provide valuable user insights regarding their behavior, needs, pain points, preferences, or mental models.

They are necessary.

This is no different in UX research — the academic studies conducted within the broader field of Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) — and the more business-oriented, pragmatic ones.

In this article, we'll look at the "scientific background," how knowledge is created, how research is born, and what role research questions play in investigation, definition, discovery, and understanding.

We'll highlight best practices for formulating research questions and explain the differences between research problems, questions, and hypotheses.

Finally, we'll present examples of user research questions, focusing on those posed in the context of user experience.

If you are interested in qualitative research, quantitative research, UX audits, usability testing, benchmarking, A/B testing, or other types of UX research (e.g., eye-tracking), you need to know about the issue of research questions.

The following article contains everything you wanted to know about research questions but were afraid to ask.

We invite you to read on!

What are the research questions?

A research question (a user research question) is the focus of the research. It organizes, structures, and directs the research. The research problem and the choice of research method influence the research question.

Research questions are the foundation; as such, they're the starting point and the point of arrival because every study uncovers something, reveals something, and allows for a better understanding.

On the other hand, it points out the "unknown" area and subsequent research problems and inspires new research questions and hypotheses. The cyclical nature of this process is the essence of science. It's the driving force behind the development of the world of knowledge.

In his book "Research Design. Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches," John W. Creswell distinguishes between research questions in qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods because of their differences.

In qualitative methods:

- Research questions are posed, but no assumptions (the research project is conducted without expectations) or hypotheses (no predictions that take into account variables and statistical tests) are made.

- Questions are posed in the most general way possible (we should avoid leading questions).

- Research questions are asked in two forms: a main question and additional questions (follow-up questions).

- Researchers seek to know as many factors as possible that can influence and condition a phenomenon.

The purpose of posing research questions (including in the design process) in qualitative research is to "discover," "explain," or "explore" also during usability testing (e.g., of mobile apps for the target audience).

Catherine Marshall and Gretchen B. Rossman, in their book "Designing Qualitative Research," distinguished and divided research questions in qualitative research, and based on that, we can separate them into various categories.

Types of research questions:

- Contextual questions seek to describe the nature of what already exists.

- Descriptive questions try to describe a phenomenon.

- Emancipatory questions aim to generate knowledge to help people, especially the underprivileged, engage in social action.

- Evaluative questions assess the effectiveness of existing methods or paradigms.

- Explanatory questions seek to explain a phenomenon or explore the causes and relationships of what exists.

- Exploratory questions deal with lesser-known areas of a given topic (e.g., the different viewpoints represented by various target groups).

- Generative questions aim to provide new ideas to develop theories and activities.

- Ideological questions are used in research aimed at developing specific ideologies of a stance.

In quantitative research:

- Very detailed research questions are posed (regardless of who we want to study).

- Research questions are much more specific.

- Hypotheses are made based on a small number of variables.

- Having expectations is common.

- Quantitative hypotheses are used to capture the relationship between variables.

An important characteristic of questions in quantitative research is their precision.

Quantitative questions can't be answered in the affirmative ("Yes") or negative ("No"); hence, we cannot use words such as "is," "are," "do," or "does."

As Imed Bouchrika notes in his article "How to Write a Research Question: Types, Steps, and Examples," quantitative research questions can be divided into three types: descriptive, comparative, and relationship research questions.

Descriptive research questions usually start with the interrogative word "what" and are intended to provide answers to a single variable.

Comparative research questions aim to discover differences between groups where a given variable occurs.

Relationship research questions investigate and define trends and interactions between two or more variables.

In mixed methods:

- Specific research questions that are appropriate for mixed research methodology should be used.

- Both quantitative and qualitative research questions are used.

We should also add Uwe Flick's remarks in his book "Designing Qualitative Research." According to him, research success depends on the quality of the research question, which should be clear and emphatic.

We'll write in a moment about the ways of formulating research questions.

The quality of the research question determines what data we'll collect and what aspects and problems will be analyzed and interpreted. According to Uwe Flick, a good research question defines the scope of necessary data that must be included in the research process.

How to formulate the right user research questions?

Formulating user research questions and asking research questions (e.g., during user interviews) are two of the most critical issues addressed when discussing the researcher's workshop.

A properly posed question makes it clear what we want to study — and, indirectly — why we want to study it.

User research questions, including UX research questions, should be:

- Clear. The more detailed and specific the question, the easier it will be to understand and identify what problem it indicates and what its scope is.

- Concise. A research question should be appropriately balanced in terms of length. It should be long enough not to leave out any important issues and brief enough not to lose its point and clarity.

- Complex. So, the simplification expressed in "Yes/No" answers is impossible.

- Argumentative. So, they open a discussion and incite honest answers rather than offer definitive conclusions.

- Focused. Concentrated on a given problem, they should be devoid of digressions and unnecessary elements.

- Realistic and rational. So that it is possible to conduct research within the given time, context, budget, logistics, and organizational frame.

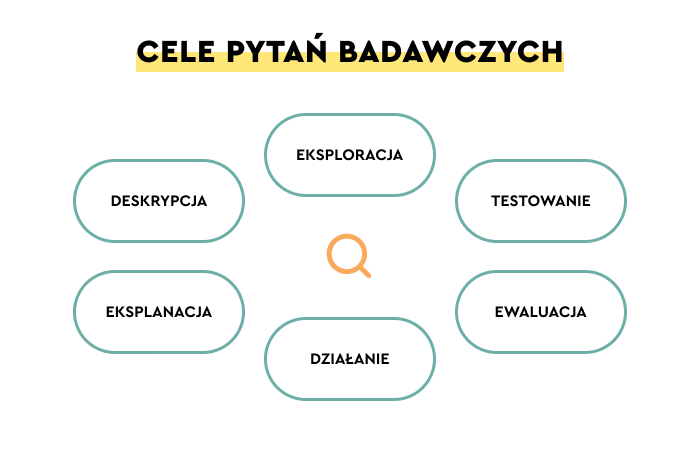

Most often, research questions are aimed at the following research objectives:

- Description

- Exploration

- Explanation

- Testing, including usability testing

- Evaluation

- Action

In the case of description and exploration, most often, a research question takes one of the following forms:

- What are the characteristics of X (for example, a user interface)?

- How does X change over time (for example, users and their expectations)?

In the case of explanation and testing, a research question, most often, takes one of the following forms:

- What is the relationship between X and Y (for example, visible during eye-tracking studies with users)?

- What role does X play in Y (for example, a mobile application in the user's life)?

In the case of evaluation and action, a research question, most often, takes one of the following forms:

- What are the advantages of X (for example, a graphical user interface)?

- How effective is X (for example, usability testing of digital products for a user)?

Imed Bouchrika, quoted above, provides a very practical method for checking whether a research question is relevant.

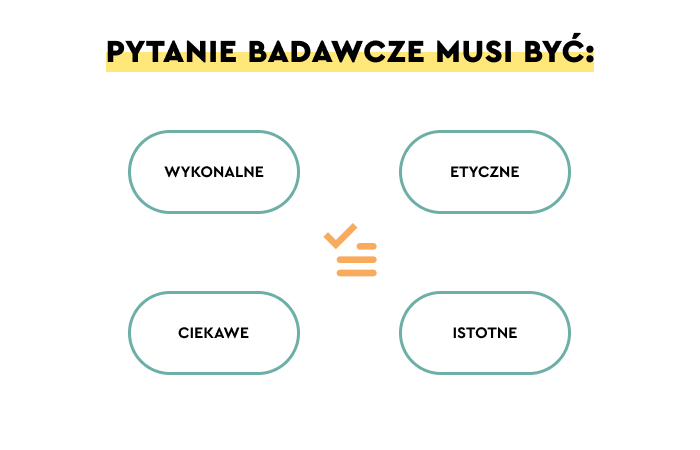

A research question must meet five fundamental criteria.

A research question must be:

- Feasible. Both in terms of realism, which we already mentioned, and the limitations of the researchers themselves, such as whether they can face the challenge.

- Interesting and/or useful. Especially in the case of UX research questions regarding usability. The practical dimension of the knowledge obtained during the research is vital — although science should not have boundaries, not everything is worth knowing. Anti-awards are the best example of this (for instance, the Darwin Awards).

- Novel. It should bring something new to the subject, to the knowledge about the problem in question.

- Ethical. It cannot violate legal norms, informal social norms, rules, or ethical norms that apply to researchers.

- Relevant. Novelty and freshness are important, but it is equally essential that the research provides value to the researcher and all or at least the majority of stakeholders.

Questions and research problems

A research problem is a much broader concept than a research question.

It's defined as a problem, issue, phenomenon, or mechanism that must be investigated, described, explained, understood, categorized, and embedded in the structure of existing knowledge.

As a part of research problems, research questions are formulated to concretize the research problems.

In the field of social sciences, six types of research problems are distinguished:

- Basic

- Theoretical

- Practical

- General

- Partial

- Specific

A research problem defines what we still don't know and what we should find out because of various objectives and benefits (teleological and practical).

A research problem focuses on pointing out what we already know and, even more importantly, what we still don't know.

Research problems have two sources:

- Heterogeneous — it's a reality itself in which something feels incomprehensible and needs explanation.

- Autogenic — it's a community of scientists who, based on the subject literature, see gaps in the knowledge that need to be filled.

Moreover, research problems based on the criterion of their usefulness and the purpose of a study can be divided into:

- Theoretical research problems that are fundamental problems solved to develop research and provide tools for solving practical problems.

- Practical research problems — their purpose is primarily to realize important social goals; they are intended to improve the functioning of the social world (e.g., more useful user interfaces).

Research questions and hypotheses

While the research questions and hypotheses may look no different to a layperson at first glance, they aren't the same.

In his study "Jak stawiać hipotezy i pytania badawcze? Teoria, wyjaśnienia, przykłady" (How to write hypotheses and research questions? Theory, explanations, examples), Andrzej Jankowski defines a research hypothesis as a statement in which a supposition is expressed about (operation, structure, influence, dependence) some phenomenon, which should be confirmed or disproved by statistical analysis.

Hypotheses organize quantitative research, define its scope, and provide a link between theory, research methods, and research itself.

A research problem, research hypotheses, and research questions are the triad (UX research is no exception) that forms the core of any study.

We can organize these three critical elements of every research (including user experience research) according to the criterion of their generality, and thus:

- A research problem is the most general.

- Research questions are more specific.

- Hypotheses are the most concrete.

We should also add that research hypotheses are made for a particular purpose—to be confirmed or refuted using statistical tools and methods.

Hypothesis verification — if it is methodologically correct and no error has been made — means that we have (relative) certainty that a supposition is "true" or "false."

The relationship does or doesn't occur.

That said, the certainty level depends on the generality of the hypothesis itself.

As a rule, the more specific, concrete, and narrow the hypothesis, the more reliable the verification result (positive or negative).

Research questions and interview questions

Research questions describe the objectives we want to achieve during a research project. They influence the rest of the study's aspects, such as the research method or research participants.

An example of a research question might be: What percentage of e-commerce mobile customers abandon shopping carts?

Interview questions are the questions that we ask the participants during a study. They are broader than research questions and leave more room for answers.

Based on the above example, the interview question can be: How often do you abandon purchasing in an online store while using a mobile device?

UX research questions — examples

We can find the best examples of research questions by reading research reports. It's also worth practicing posing research questions because it's very easy to make mistakes, especially if we're a novice researcher.

Quantitative research questions examples

For example, a research question — formulated for quantitative research — that is too general, vague, or unspecific might read as follows:

How do people react to the interface?

The question needs to be more specific because it operates with a category of people that can't be studied. It's physically, time-wise, organizationally, financially, logistically, etc., impossible to study several billion people.

The question needs to be clarified, as it is unknown to whom and to what it refers.

It's unclear what type of reaction is of interest to the researcher, such as whether they mean emotional, behavioral, conscious, involuntary, or automatic reactions.

The question is also unclear because it doesn't specify the concept of an interface. What kind of device is this interface on?

On what application? What type of interface? Reaction to which interface element is going to be measured?

Finally, the question doesn't imply the problem's importance. It's impossible to deduce why such a problem is worth the effort.

The above research question, to sound much more concrete, understandable, clear, and realistic, should read like this:

How long does it take American men between the ages of 25 and 30 to find an ADDE chair in Ikea's online store using an internal search engine?

Qualitative research question examples

In qualitative research, research questions are often formulated to explore, evaluate, probe, discover, and describe research participants' expectations, impressions, and problems.

For example:

How would you rate your shopping experience in Ikea's online store?

Express your opinion using a scale of 1-10, where a rating of 1 means Very Bad Experience and 10 means Fantastic Experience.

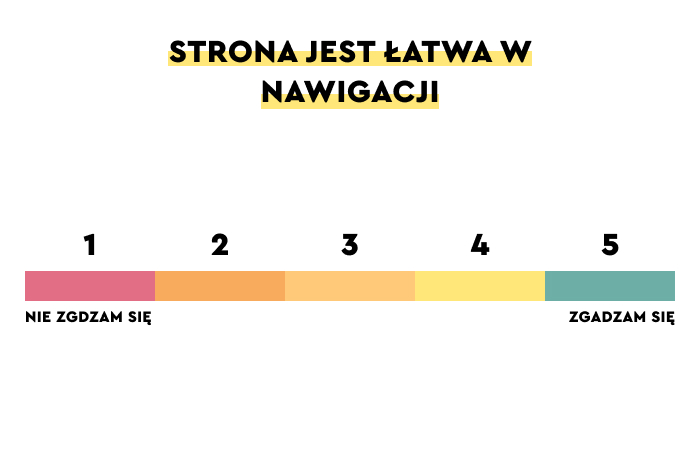

How strongly do you agree with the following statement: "The ordering process at the Ikea store was easy."

Express your attitude with one of the statements from the following scale:

- I strongly disagree

- I disagree

- I neither agree nor disagree

- I agree

- I strongly agree

Of course, this is only a small sample of research questions. They will vary considerably depending on the research method, the purpose of the study, the research problem, the methodology, and the respondents.

UX research questions. Summary

- Modern science relies on research problems, questions, hypotheses, experiments, replication of research, and meta-analysis.

- Relevant problems and research questions are the starting point and form the horizon of our knowledge of the world and phenomena.

- User research questions provide valuable insights into user preferences, behavior, pain points, needs, and mental models.

- How to formulate research questions — the purpose of posing research questions in qualitative research is to "discover," "explain," or "explore."

- Quantitative questions can't be answered in the affirmative ("Yes") or negative ("No"); hence, we can't use words such as "is," "are," "do," or "does."

- Research questions can be divided into descriptive, comparative, and relationship questions. Different types of questions will help us achieve different research goals.

- Research questions should be clear, concise, complex, argumentative, realistic, and rational.

- A research problem is a much broader concept than a research question. It's defined as a problem, issue, phenomenon, or mechanism that needs to be investigated, described, explained, understood, categorized, and embedded in the structure of existing knowledge.

- A research problem focuses on pointing out what we already know and, even more importantly, what we still don't know.

- A research problem, hypotheses, and questions are the triad that forms the core of any study.

- The research process and the design process are intertwined, and their common link is the research questions.